- Details

- Last Updated on Friday, 04 January 2019 03:04

Biography 1968

Escape from the Communist Nightmare

Escape from the Communist Nightmare

Life in Freedom

In January 1968, Alexander Dubček, General Secretary of the Communist Party in Czechoslovakia, set out to reform the communist system, attempting to put a "human face" on an inhuman system. His only important reform was the lifting of censorship on March 15, which created a free press. Shortly thereafter, a communist politician Alois Indra delivered a speech in Ostrava denouncing Dubček's reforms, and advocating a return to the previous repression. I responded by an article in which I equated communism with nazism. I had no fear of reprisal at that time because of freedom of the press. My article even appeared in several leading newspapers, including Rudé Právo (Red Truth), the communist party newspaper, Mladá Fronta, etc..

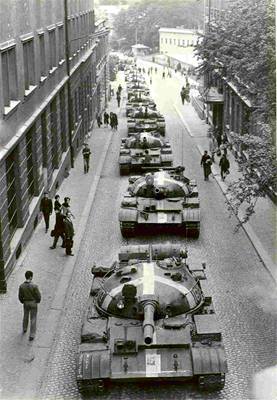

Uneasiness with Dubček's reforms on the part of the Soviets lead to the invasion of Czechoslovakia in August, 1968. I was attending a Geological Congress in Prague at that time, when a sympathetic agent of the Czechoslovak secret police (StB, guided by the minister of Interior Pavel), who was himself in the process of escaping, informed me that they had to pass my name onto a KGB blacklist of subversives. My crimes? Perhaps, because I had written the incendiary article several months before. In addition, I had long been under suspicion since I corresponded with American geologists in connection with my work, contrary to official policy at the Geological Survey. Shortly before my escape, I burned several kilograms of my correspondence with these people so as not to endanger my parents. Likewise, the previous autumn, I had been accused of attempting to escape from Czechoslovakia and encouraging my former wife to do the same. Conviction on those charges would have led to two terms of imprisonment of two years each. 22 people were investigated by the secret police in connection with this incident, said me the responsible officer.

It was at that point that I decided to escape from that country. I asked the secret agent (who had told me that the Secret Police of Czechoslovakia [StB] had passed my name to the KGB blacklist), about how to escape. He knew which border crossings were not yet guarded by the Soviet invaders, but this information would only be valid for the next 48 hours at most. I was given this information on Thursday August 24, so I would have only until the following Saturday to escape.

I was acquainted with Geoffrey C. Russell-Jones (photo on the right from Sky Riders directed by Jindřich Polák, 1968), a British businessman for whom I had acted as a go-between when he sold a computer (of his company, Clary DE-600) to the Geological Survey. I convinced him to take me and my family with him in his Aston Martin DB6 sports car (photo on the left; the famous car of Ian Flemming's James Bond, "007").

I was acquainted with Geoffrey C. Russell-Jones (photo on the right from Sky Riders directed by Jindřich Polák, 1968), a British businessman for whom I had acted as a go-between when he sold a computer (of his company, Clary DE-600) to the Geological Survey. I convinced him to take me and my family with him in his Aston Martin DB6 sports car (photo on the left; the famous car of Ian Flemming's James Bond, "007").

I went home to tell my wife that we had to escape, but she believed that it would be a two-weeks vacation to the West, after which we would return. By coincidence, her name day, Helena, was on August 18, and as a present, I managed to obtain for her a passport (which was only legally possible under Dubček's reforms). So I gathered my wife and 2 1/2 year old daughter, took my Italian espresso machine La Piccolina La Carimali (photo on the right), and began the trek to freedom. In so doing, I left everything behind, including parents and friends. Yet another facet of the cruelty of the communist system is that I never saw my father again after having escaped (he passed next year).

It had been my first intention to go to London where I had an invitation from Imperial College. We had intended to travel through West Germany on the way to England. Because the West German trade mission in Prague, which could grant visas, was blocked by Russian tanks, we went to the Austrian embassy instead, where, after midnight, we were given our visas.

With Geoffrey, we started heading south to Linz, Austria, where along the road in Czechoslovakia we saw only signs pointing to Moscow (the Czech suggestion for Russians), but happily no tanks. At the border itself, the Czech guards were friendly, and even put our daughter's name into my wife's passport, thereby making it legal for her to be taken across the border. In that respect, the border guards were sympathetic to our plight, and knew full well what we were doing.

Once across the border, I saw a world of colors that were unknown in the dismal shops and on the gray and dirty streets of communism. Our first stop was in Linz, where we ate lunch and went bowling! Afterward, in Salzburg, we stayed in the pension "Haus Paracelsus" while waiting for visas for West Germany, and Geoffrey had to continue his way to London without us.

Although I wanted to immigrate to the USA, where I had invitations

Although I wanted to immigrate to the USA, where I had invitations  from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and Rice University, my wife wanted us to remain in Germany to be close to her family. She didn't even want to go to England (I had an offer from the Imperial College, London) because she had a fear of English - 'a language, in which one speaks differently from writing'. I called my German friend Dr. Max Linseis, Selb, Germany (photo on the left) for help. I met him on his products exhibition in Praha in 1966 and visited him in Selb in 1967 — he was interested in my settling tubes. He arranged a unique contact for me with his schoolmate, Prof. Dr.-Ing. Hans Rumpf (photo on the right), Director of the Institute of Mechanical Engineering, Technical University of Karlsruhe. So, I with my family settled for 2 and 1/2 years in University Park at the University of Karlsruhe, where I had an Alexander von Humboldt postdoctoral fellowship.

from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and Rice University, my wife wanted us to remain in Germany to be close to her family. She didn't even want to go to England (I had an offer from the Imperial College, London) because she had a fear of English - 'a language, in which one speaks differently from writing'. I called my German friend Dr. Max Linseis, Selb, Germany (photo on the left) for help. I met him on his products exhibition in Praha in 1966 and visited him in Selb in 1967 — he was interested in my settling tubes. He arranged a unique contact for me with his schoolmate, Prof. Dr.-Ing. Hans Rumpf (photo on the right), Director of the Institute of Mechanical Engineering, Technical University of Karlsruhe. So, I with my family settled for 2 and 1/2 years in University Park at the University of Karlsruhe, where I had an Alexander von Humboldt postdoctoral fellowship.

Having received the German visa in Salzburg in September, we took train toward Karlsruhe and interrupted our trip at München/Munich on Tuesday, September 17, to visit RFE/RL, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, the Czechoslovak Department on Wednesday, September 18. The head of the News Department, Bohuslav J. Holý, welcomed us in Germany and guided through the Czechoslovak Department. It was impressive to meet persons we knew as forbidden radio voices only.

In Karlsruhe, we had been living in Gastdozentenhaus Heinrich Hertz, Engesser-Strasse 3. it was for the first time that I could remember, I slept well at night, knowing that the slamming of a car door outside my window at 3:00h in the morning did not mean that the StB (Czechoslovak Secret Police) or KGB was coming to take me to prison (communist concentration camp, Czechoslovak Archipel Gulag).